The Runaway Quilt Project is an endeavor for LIS 697 Digital Humanities at Pratt Institute. Currently this project lives on a WordPress blog, where digital research about quilting during the slavery era, before and after Emancipation, is aggregated. However, the end-of-semester deliverable, which preserves work done over several months, is a static non-digital ‘document’ – a dataquilt.

This two-sided quilt, titled Maker Unknown, archives the data aggregated online January – May 2012.

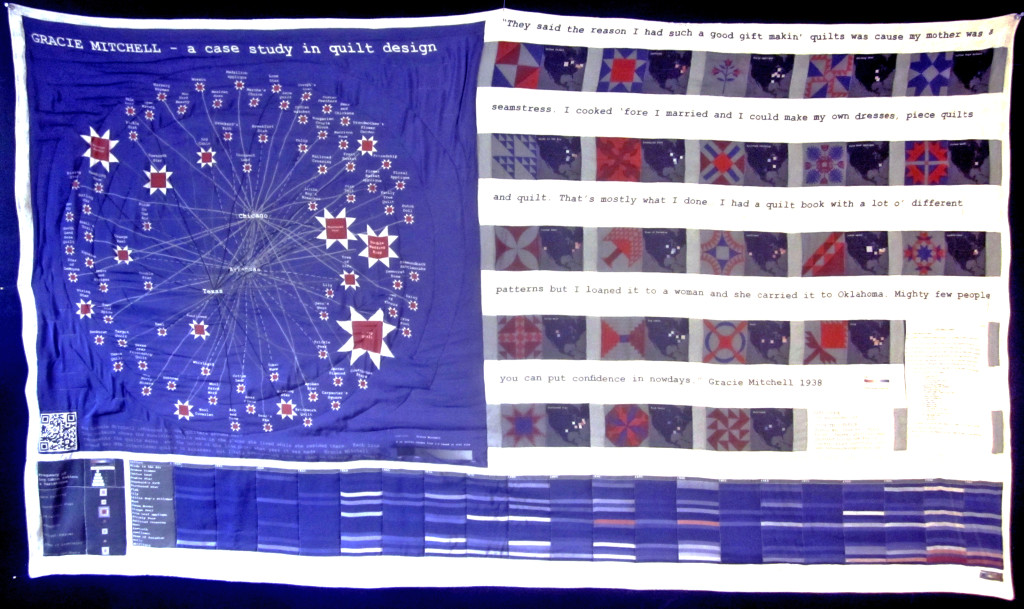

This two-sided quilt, titled Maker Known, archives the data visualizations created January – May 2013.

The Oral Textile Tradition

As Abby Smith discusses in “What is Preservation and Why Does it Matter?” regarding the humanities in general, quilters “rely heavily on retrospective as well as on current resources”. Most of the history and methodology for creating a quilt was passed down orally, and the core data in the RQP consists of quotes transcribed from interviews with ex-slaves. Their data has migrated from audio recordings to paper documents to digital files and are essential connections to the past. Quilters continue to share unique information in this oral way, while the majority of printed information (today) on quilting is redundant and focuses on methods. This means that in order to learn quilt history, one has to engage in the process or seek out museum exhibitions and collections, which can be few and far between compared to the plethora of outlets for other artistic mediums. Everything I have learned about quilting, until recently, came from my grandmother and her friends and from attending quilt guild meetings and shows, where you strike up a conversation with someone near you while examining the same object/listening to the same presenter, or a more seasoned quilter interrupts you while working to correct or teach you. The heart of the project has always been migration of the oral tradition to the digital. However, although quilters in the future may be more digitally savvy, the online presentation of research is not the ideal way to engage present day Baby Boomers or the GI generation, some senior quilters are around the same ages as the ex-slaves/quilters interviewed for the WPA Federal Writers Project.

Migration

The most appropriate way to preserve the RQP is to use network analysis to design a quilt top capturing the essential information. This will ensure that data in the RQP is available for several centuries, at minimum. Smith describes migration as follows,

“Digital information is transferred, or rewritten, from one hardware/software configuration to a more current one… Often, a digital repository where data are stored will reformat or “normalize” data going in to the repository; that is, the repository will put the data into a standard format that can be reliably managed over time… digital files translated into another format will lose some information… ranging from formatting or presentation information to potentially more serious forms of loss.”

Unfortunately, the losses that will occur during this migration are essentially those features that make the project “digital.” The data collected will move from the computer/Wordpress blog configuration to a textile/quilt design configuration. Reformatting or normalizing the data in this way means that it can be reliably managed over time; the quilt and information in it will be easily accessible, and when it is finally placed in a museum collection it will be in a format curators are familiar with and can reliably store. Also, the information will be easily accessible to future quilters through a museum’s online catalog with surrogate images, as well as through physical visits to the site to view the 3D object.

The interactive features of the blog, annotation and commenting, will be the most salient pieces lost. However, migration of the information will be the best way to actually provoke conversation with the community that does not generally read scholarly journals or surf internet blogs. Once the information is static on a quilt top, the conversation will continue by holding a quilting party, taking the quilt to bees and guild meetings, and entering it in shows. In the world of sequential art, ‘readers’ make meaning between the panels; they look at static images and the brain connects the dots, creating a logical explanation for the action that occurs in the gutter, which then explains the next sequential static image. Similarly, by presenting the static information on a quilt top, quilters who view it will make their own meaning ‘between the blocks’. To capture the oral commentary and discussions that my grandmother and other quilting peers engage in, a pocket will be placed on the quilt where viewers can leave comments, which will be added to the digital blog. Keeping track of these ‘collaborators’, and continuing this research through a doctoral program, it will be possible to expand on the digital information and oral history for both a dissertation and a book. The book format will likely supersede the quilt, and definitely the blog, over time, but the quilt will last a few hundred years in ideal storage conditions.

Persistent Object Preservation

Another method promoted by Smith, persistent object preservation, “envisions wrapping a digital object with the information necessary to recreate it on current software.” Smith continues,

“This approach is conceptually related to the efforts of some digital artists, creating very idiosyncratic and “un-normalizable” digital creations, who are making declarations at the time of creation on how to recreate the art at some time in the future. They do so by specifying which features of the hardware and software environment are intrinsic and authentic, and which are fungible and need not be preserved.”

In the case of the RQP, the features of the environment which are intrinsic are the quotes from WPA interviews, a map of the east coast with patterns and dates, and graphs from Google Ngram viewer. Each of these elements is authentic in that each consists of information gleaned from a single primary source collection: the Library of Congress slave narratives, the International Quilt Study Center & Museum online database, and the Google Books digitizing project. The first and last organizations provide enough samples for reliable statistical work, and the IQSCM offers a qualitative analysis of digital surrogates.

Neil Fraistat writes in The Function of Digital Humanities Centers at the Present Time (Debates in the Digital Humanities 2012) that inter/trans/multi-disciplinarity is empty unless it implies “changes in language, practice, method, and output”. Rather than a digital object, the RQP will result in a textile object wrapped with the information necessary to re-engage oral history at some time in the future. To balance the textile deliverable, the process of making it will be captured on digital video and uploaded to the RQP WordPress site, and the source code for the website could easily be printed or embroidered on to the back of the quilt. Using the images and graphs on the front of the quilt and the source code on the back, future information professionals and/or quilters would be able to recreate the digital humanities project. Choosing to use persistent object preservation in this way satisfies several principles and values for digital humanitarians identified by Diane Zorich: cross-disciplinarity, civic and social responsibility, rethinking traditions, and giving equal value to theory and practice.

Steps for Preservation

- Complete blog

- Design network

- Begin video recording of quilt production.

- Print images, graphs, & source code.

- Create Gracie Mitchell’s 22 quilt blocks.

- Assemble quilt top.

- Assemble quilt layers.

- Quilting party!

- Add pockets to quilt.

- Take pictures.

- Copyright quilt design.

- Upload video online.

- Enter in to exhibitions, visit guilds.

- Store properly.

- Donate to IQSCM or comparable institution.

Ultimately, as the RQP was based on the interviews done with former slaves, and preserving this project means engaging current quilters in conversation in order to capture the information that they possess for the future. Many of the women in quilt guilds are elderly, and it is imperative to link their experiences to those who came before them and are now able to “communicate” with us and pass down information. These women are the ideal interpreters of the RQP data, and by engaging them in conversation, and traveling with the quilt, I will be able to keep the project/conversation alive and return to the digital medium better armed to produce a 2nd edition quilt in the future.

An important analog element of this process will be quilt preservation. According to Judy Schwender, the curator of collections at the National Quilt Museum, the worst thing you can do with a quilt is fold it in to halves and quarters and store it in a cedar chest – a tradition in American quilting culture that has not favored the preservation of thousands of potentially revealing historical documents. In a 2008 interview with the WSIU NPR Public Broadcasting, stating, “We can only judge the past on the artifacts that survive,” Schwender gives the following techniques for quilt preservation:

- Spot clean the quilt only when necessary; never wash it except for extreme situations (vomit, blood, urine, etc.).

- Vacuum a quilt using fiberglass or nylon screening (bind edges on sewing machine). Use the upholstery tool on the vacuum cleaner and hold it just above the screening, going lightly back and forth to remove degraded cellulose (degraded cotton), dust, and dirt.

- Store in an acid-free box, with (preferably unbuffered) acid-free paper.

- Crunch up the paper and place it between the layers of the quilt as it is rolled. Use a sausage-shaped wadding of paper for the final lengthwise folds, and place tissue underneath and on top of the quilt in the box.

Quilts should obviously be stored in a dry, climate-controlled environment. Other aspects of preservation that are important to an archivist taking in a quilt is the inclusion of detailed metadata, something missing from almost every quilt created prior to the 20th century that survives. The International Quilt Study Center and Museum considers documentation heavily in acquisition decisions, asking “What is known about the quilt and its maker?”, “Who made the quilt?”, “Where was the quilt made?”, “When was the quilt made?”, and “Why was the quilt made?” The metadata that the IQSCM tags on to their objects includes the following elements:

Primary pattern

Title

Quiltmaker

Origin country

Origin state/region

Date

Style type

Predominant technique

Exhibitions

Brackman #(s)

Dimensions

Primary techniques

Primary fiber

Primary fabric

Quilt stitches/inch

Binding

Inscription type

Other

In addition to including the source code on the back of the quilt, it will be important (as it ALWAYS it) to place a label on the quilt. In the case of the RQP, a suggested citation will also be included on the back, front, or border of the object. Finally, I will protect it with my life until I am ready to donate it to a museum!